Introduction

With the blockade in place the Soviets were confident that they could force the westerners out of Berlin.

In the western capitals there was consternation and a feeling inevitability that they would have to leave Berlin. That it would be better to leave sooner rather than be seen to be forced out later.

General Clay (the U.S. Military governor of Germany), had been due to retire, and control of Germany passed from the military to the State Department. However, with the looming crisis it was decided that he would remain in post and the transition to civilian governance be postponed.

On the imposition of the blockade Clay proposed driving an armoured column through to Berlin. A solution so fraught with problems, the most serious of which was war with the USSR, that it was quickly vetoed by higher authority.

Although there had been regular flights to Berlin, Clay, and Robertson (His British counterpart) decided to use the available aircraft to start ferrying material to Berlin whilst waiting for a political decision.

The first flight of the airlift took place on June 26th.A young pilot was ordered to fly to Berlin although it was already late. On landing in Berlin, he was ordered to return immediately the plane was unloaded.

On his return he was met by his commanding officer who asked how the flights had gone. When he replied there was no problem, that it was routine. His CO said, “great the Soviet had indicated they would shoot planes down”.

So, it began!

Politics

Although President Truman privately committed to staying in Berlin with his now famous comment, “We stay in Berlin Period!” there were no forceful public statements.

In the absence of public statements from the government Clay and Hawley, (Military Governor of Berlin), did make statements about not being forced out.

Within the US political and military establishments there was a general feeling that an airlift would not succeed and would certainly not be a practical solution after the north European winter set in.

With strong encouragement from Ernest Bevin the British Foreign Secretary and the Royal Air Force (RAF), it was decided increase the resources available for the airlift, if nothing else it could buy time whilst a diplomatic solution was achieved.

Clay contacted General Curtis LeMay (Head of the Airforce in Europe) and asked if they could ship coal to Berlin. According to legend LeMay replied that the air force could ship anything anywhere.

Operation Vittles

LeMay placed General Joseph Smith in charge of the operation, with the comment that it would only be for a few weeks.

Smith named the Airlift “Operation Vittles”, (The British designation was “Plain Fare”) and set about getting more men and planes.

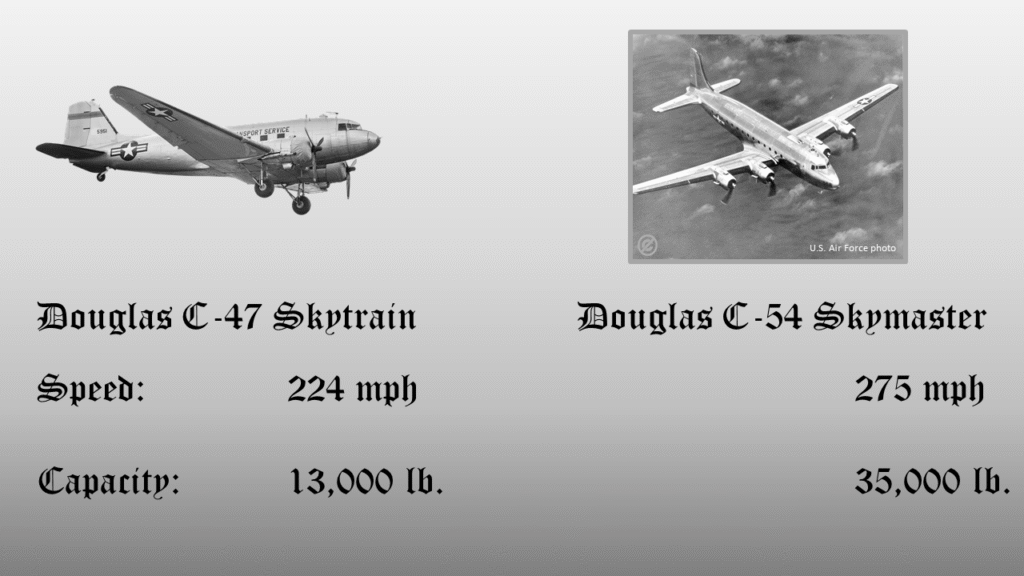

Initially the airlift was operating the ancient C-47 or Dakota, indeed some were still in desert camouflage from the North African campaign, or the black and white striped wings of the D-Day landings.

Apart from being old the main limiting factor of the C-47 was its low payload.

Clay and Smith immediately requested the newer and larger C-54s

Crews and aircraft were transferred in for the U.S., and as far afield as Hawaii and Guam. The British were initially able to ramp-up more quickly, due to proximity, but were soon surpassed by the American effort.

As more men and aircraft began to arrive the facilities at the bases were quickly overwhelmed and living conditions deteriorated.

Conditions for the families left behind at short notice were also poor and there were not adequate provisions made to ensure the welfare of families often newly arrived at overseas locations.

Very quickly men and machines started to deteriorate, and the spares were quickly depleted. The spares stock levels were set for normal operations and not for the round the clock operations now in effect.

Despite all the frantic effort the airlift was not coming close to the 4500 Tons/day required to meet Berlin’s needs. (1200 Tons/day was the best so far)

With requests for more planes, discussions continued as to the best course of action. Despite President Truman’s “We stay in Berlin Period!”, the general feeling was to get out.

Few in the military believed that the airlift was viable, and the Airforce did not want to pour resources into what they saw as a forlorn hope.

They wanted to get back to the “real” business of the Airforce.

There was a genuine concern, that if most of the counties transport aircraft were in Germany, they could all be destroyed if war occurred, crippling the US war effort.

In addition to the lack of resources the runways in Berlin were deteriorating rapidly.

The main organizational problem was that the operation was being run by “bomber” people and not Transport Command.

If something did not change the prophets of doom would be proven correct.

The New Man

Did anyone have experience running an airlift?

Happily, YES.

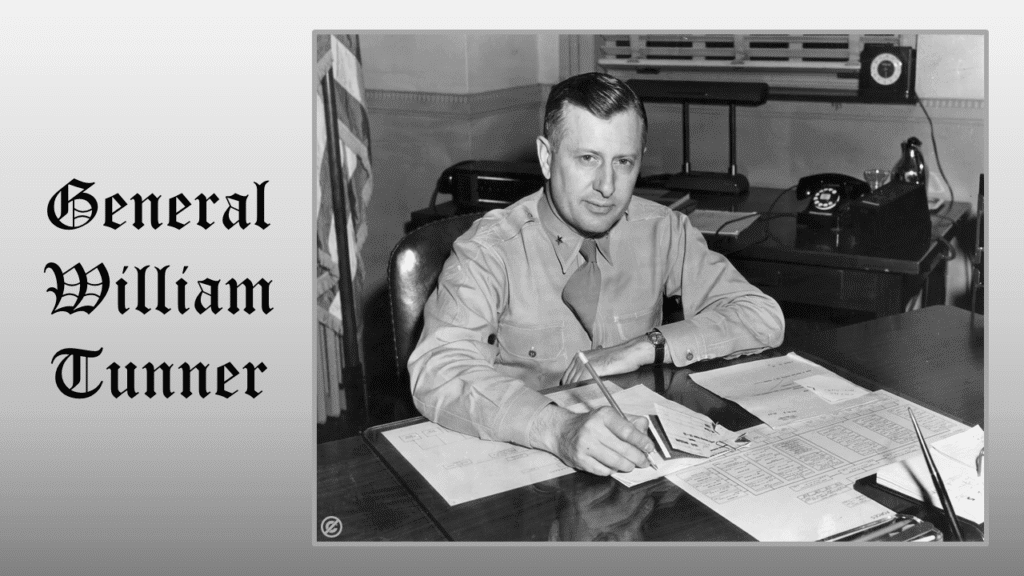

General William Tunner who was, as he put it, currently warming the bench at the Pentagon, had run an extraordinarily successful airlift operation from India to China during WWII.

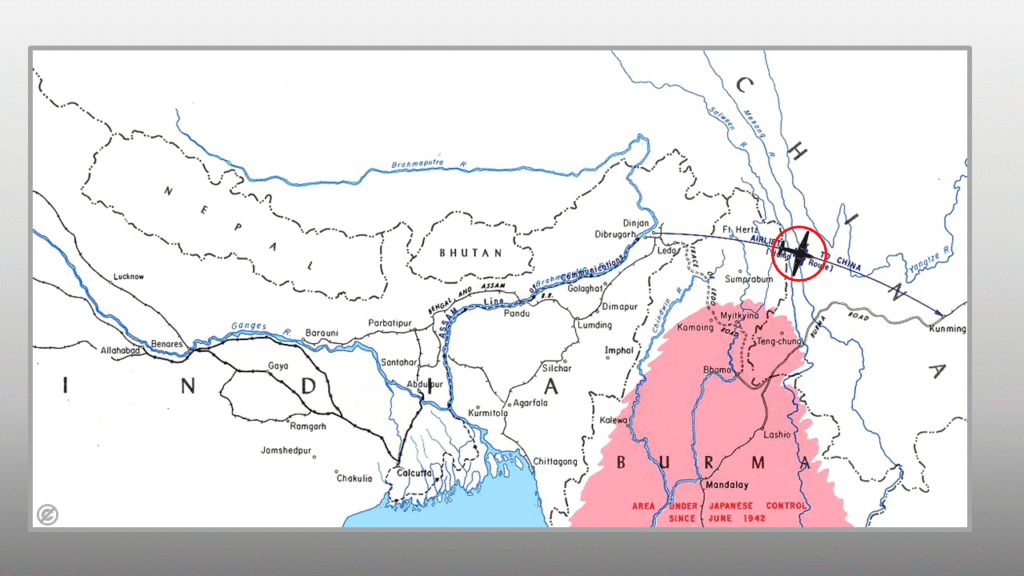

This airlift was called “The Hump” because the route from India to China crossed the Himalayas. The airlift was supporting our Chinese allies who were also fighting the Japanese.

When Tunner took command in September 1944, the Hump was the graveyard of military careers.

The Hump was sustaining casualties higher than those of the bomber group in Europe, and consequently moral and discipline were low.

The route was extremely hazardous and when it was not passing high over the Himalayas it was over impenetrable jungle.

Any crews force landing or bailing out had little chance of survival and recovery.

Tunner was a workaholic and expected the same from his team and would earn the nickname of “Willie the Whip”.

Tunner moved in and immediately imposed discipline and structure.

- Aircraft were better maintained

- Crews were better rested

- Crews were trained in safety and jungle survival

- Procedures were put in place

- Targets and statistics were used to control and motivate

Accident rates were lowered even though the number of flights and the overall tonnage increased dramatically. By the end of the war Tunner had created an efficient smooth-running operation.

Airforce recognized the need for change and Tunner was appointed to head the airlift.

With his hand-picked team he headed for Germany, arriving on the 28th of July 1948.

He reported to General LeMay and was received in a frosty manner.

His duties were spelled out and it was made clear to him that he would report through the Airforce command structure and was not to have direct contact with the other services or the civilian authorities.

He and his staff then went to the offices assigned to them.

They found a ramshackle building, the rooms bare except for rubbish, and a layer of dust and cobwebs.

A rather inauspicious start.

Could “Willie the Whip” turn things around?

Conclusion

The western allies were in a bad situation, they had not anticipated the Soviet move, and had no contingency plans in place. There had been little, or no risk analysis done.

Even if one considers the Soviet blockade as a “Black Swan “event there should have been some provisions in place for such an event.

Responsibility for the airlift was placed in the hands of a group, who did not believe it could succeed and did not consider it the “real” work of the Airforce.

Additionally, the group given the task were also not competent to carry it out.

What can this teach us as project managers?

- Perform proper risk analysis and have a mitigation plan in place.

- When assigning personnel

- Ensure they are committed to the project

- Ensure they are competent to carry out the work

- Ensure that they get the full support of other departments

- Ensure that they are given the support and resources